|

|

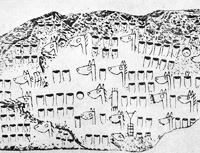

Courtesy of Oxford University Press Said to be a pedigree chart from 5000 years ago. The heads of the horses display convex, flat and concave profiles, and their manes are of erect, hanging and maneless types. Amschler, Wolfgang, The Oldest Pedigree Chart: A Genealogical Table of the Horse and Pictures of Horsemen Dating Back 5,000 Years. J. Hered. June 1, 1935 26:233-38. Deep-Rooted Anomalies in Female Families Equine Genetic Genealogy Bend Or vs Tadcaster Bonny Black and Family 39 Family 23 and Early Sources Wyvill Mares Distribution of Thoroughbred Matriarchs in the Equine Mitochondrial Tree |

The Tradition Long before official stud books were compiled, private records were kept by owners, and mention was sometimes made in early racing match books, and even the newspapers of the time, of the sires or dams of the runners. However such records gave scanty information and were probably not readily available to all race followers. The horses themselves, when they changed hands or were advertised, often came with an affadavit or certificate that stated their pedigree, attested to by the owner or some other person of note. The advent of the racing calendar provided a basic means of identifying the horses and their owners. Mr Cheny, who was said to have spent many an hour in quest of a pedigree, published his first racing calendar in 1727. To his credit he identified thousands of horses, tracing their pedigrees as far back as was possible for him. However, by the time the first stud book appeared in 1791, Mr Weatherby was already lamenting that it was too late to collect the pedigrees of the earliest horses. Efforts were made by those who followed Mr Cheny to complete pedigrees by consulting with owners and breeders and with the race records. Over time the details disappeared and pedigrees became more refined, often depending on tradition for the way they were presented. However, much confusion and conflict still exists. For example, there are at least four taproot mares for Family 6, two for Family 9, two for Family 12 and other families appear to overlap in some places and disconnect where they should not. Pedigree recording cannot have been easy. There were no rules for spelling or grammar or indeed for the way a pedigree should be recited. Poor handwriting probably accounts for many irregularities. The practice of naming offspring after their parents, even for numbers of generations, contributed to the confusion and several centuries later inspired Mr Prior to call it reprehensible. Horses were also known by different names to different people, for example, if John's Arabian was sold to James, then at least some people only knew that Arabian by one name. Names were usually bestowed on horses after they had achieved success on the racecourse, so, for example, a horse may well have raced under the name King Herod Colt for as long as it took him to win a race, however, more than one person had more than one King Herod Colt in their racing strings. Even after having demonstrated merit on the turf, mares were often still referred to as a subset of their sire, as being a daughter of Flying Childers may well have outweighed her galloping prowess. While today we might expect to see a tabulated pedigree with a horse's ancestors carefully placed in the correct position, early pedigree compilers did not have this tool. They were recorded as one person would recite them to another, and as such were subject to the memory and organisational skills of the speaker. Reading them requires acute attention as details are not always presented in an order that might be expected. Over the years we've come across a fair selection of mangled, garbled, confused, ambiguous and misleading pedigrees. They range from the simple to the epic. Byerly crosses may have been just the thing: Mr Pullen maire of chesnut Byerly came out of old Byerly and Mr Pullen's Arabian Hors, did cost me 50 guinis. Despite the possibility of a nurse mare and a surrogate mother, this horse still has too many dams: The famous Horse called Favourite, just Landed from England, bred by Hugh Bethell, Esq in Yorkshire, whose Pedegree is certified by Mr Bethell as follows. Favourite was got by my Arabian, his Dam by old Buffler, his dam by yellow Jack, his Dam by Curwin’s Arabian, his Dam by black Legs, and she out of Gray Royal, of the same Kind of Mr Leeds Spanker; the Curwin Arabian Mare was bought by Sir Marmaduke Wyvill of Lord Darcy of Sedbury, and the Account of his Pedigree I had from my Lord. Truth in advertising may have originated here: This is to give Notice, that Mr Henry Jaques of Constable Burton near Middleham in Yorkshire, keeps a fine Stallion, which is near 15 Hands high, clear of all natural Infirmities, beautifully Shaped, a good Bay, and well Marked. He was got by old Tifter, and out of a Mare which was Mr Pullein's, call'd Garnett. It is hoped, that this Pedigree (being short) will not be liable to so many Mistakes, as are frequently found in those that are long; thus much more however may be truly added, that Tifter was a Son of the Thoulouse Barb, which got Bag-pipe; and several other good Horses in England of a later Date than 40 Years ago, tho' it is not pretended he got them All; particularly Leeds, which was generally allow'd to have been a Son of Mr Leed's Arabian. The Price of a Leap this Year will be only Half a Guinea: But it is hoped the next Year he will be thought to deserve a Guinea, and then his Pedigree shall be longer. Nevertheless compilers persevered and the stud books of the world are a tribute to their collective labours. |

|

|

|

"Twilight", the Thoroughbred mare sequenced for the Horse Genome Project |

The Science During the 20th century, requirements for blood-typing and, later, recombinant nuclear DNA-based proof of parentage, reduced then eliminated the potential for ambiguity and error in the pedigrees of official record entered since inception of such testing. Currently, the International [TB] Stud Book Committee requires DNA proof of parentage of its member registries for all foals of 2002 and later. Most larger TB registries required such proof before before then. Non-recombinant forms of DNA (maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA and male-specific Y chromosome nuclear DNA) have proven useful for studying the accuracy and integrity of the historic matrilineal and patrilineal record. The accuracy, as confirmed by analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), of the record of that most prolific Thoroughbred matrilineage, Family 1, stands as one of the most noteworthy achievements of the early compilers. A single mtDNA type has been documented in one or more contemporary descendants of all 22 designated family 1 branch mares, the foaling dates of which span 200+ years, remarkable conservation for so large a group. In 2005 the domestic horse was one of 24 mammals selected by the National Human Genome Research Institute to have its genomes fully sequenced for purposes of comparison and contrast with the human genomes The horse contributing the DNA for this endeavor was a Thoroughbred mare bred and raised at Cornell University. Since completion of the Horse Genome Project in 2007 and subsequent development of DNA microarrays that "read" the status at variables throughout the recombinant equine nuclear genome, knowlege gleaned from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) has been applied to study of everything from diseases to conformational and performance attributes, to coat colour patterns in a variety of horse breeds/types including the Thoroughbred. This information continues to expand our knowledge of the Thoroughbred, contemporary and historic. |

|

|

|

Racing At Newmarket

Racing At Newmarket Peytona and Fashion, match race, 1845  Piggin String (TB b c 1942 Ariel - Wiggle by Pennant) Family 9-f. AQRA Champion Quarter Running Stallion 1945-46 |

Speed and the Thoroughbred Speculation about how to define and optimize the heritable component of superior racing performance probably began shortly after domestication. Only within the last decade, however, did it become possible to qualify and quantify that component with specific information from the equine genome itself. No breed has been subject to more scrutiny in this regard than the Thoroughbred. Multiple research groups quickly homed in on evidence from GWAS that the myostatin (MSTN) complex on equine chromosome 18 (ECA18) is a target of intense selection pressure in the breed. Initial reports focused on a derived variant at a single MSTN locus, representing it as a strong predictor of better speed (if not class), probably due to its effect on muscle fiber type proportions. Subsequent studies have conclusively demonstrated that a derived variant at another MSTN locus is more functionally signficant in that regard. These two derived variants are usually but not always inherited together. That positive selection pressure favoring this combination of derived variants in the TB is of relatively recent origin is suggested by findings from testing of the remains of historic sires foaled between 1764-1930 (Bend Or, Donovan, Eclipse, Hermit, Hyperion, Persimmon, Polymelus, St. Frusquin, St. Simon, Stockwell, and William the Third). None of them were found to have the derived variant that attracted initial interest on either copy of ECA18. (They were not tested for the more functionally significant derived variant that usually accompanies it.) The less functionally significant of these two derived MSTN variants occurs without the other one in a geographically diverse array of equine groups, including 2300 and 4100 year-old archaeological specimens from the Kazakh steppe. However, it occurrence in combination with the more significant derived variant has so far not been documented in any horse populations other than the American Paint, Andalusian, Florida Cracker, Mangalarga Paulista, Missouri Fox Trotter, Quarter Horse, Thoroughbred, and Uruguayan Criollo, raising intriguing questions about when, where, and how the combination came to exist in the TB 'gene pool'. There is no evidence that this combination of derived MSTN variants is under positive selection pressure in any breed in which it's known to occur except the American Paint, the Quarter Horse and the Thoroughbred. Not surprisingly, the combination occurs in the Paint and QH at even greater frequency than in the TB. |

|

|

|

Charles II (1630-1685) and Nell Gwyn attend Newmarket races. At the post are a bay, a grey and a buckskin. |

Equine Coat Colour and Markings 101 Few if any Thoroughbred registries require the same scientific standard of proof for coat colour that is now mandatory for parentage but it is quite possible to establish base coat colour and some modifications to it from genome-based information. It was the colour of the flowers and seed pods of his plants that revealed to Gregor Mendel the fact that heritable traits may lie hidden for one or more generations. Inheritance of base coat colour in the horse, determined at the MC1R locus on chromosome 3, follows the simple pattern Mendel observed in his plants. There are two alleles (gene variants), red and black. Red is recessive to black, i.e. can remain hidden. It will be expressed only if both copies of chromosome 3 carry the red allele (e). Black (E) will be expressed whether that allele is on one or both chromosomes (EE, Ee). Grey or non-grey, controlled on chromosome 25, also follows simple Mendelian inheritance. Grey is dominant to non-grey. It need be present only on one copy of the chromosome to "trump" whatever base coat colour is defined at the extension locus. Eventually, that colour will be completely replaced by grey. There are, obviously, many modifiers that create the various patterns and shades of base coat colour observed in the horse. A few of these modifiers have been identified and mapped to a particular area of the equine genome. Undoubtedly more remain to be found. Perhaps the most obvious of the modifiers is the agouti locus (ASIP) on chromosome 22. Several alleles there variably restrict expression of black pigment, producing bay horses. "Bay" encompasses everything with black ears, mane, legs, and tail but some visibly lighter colour on the body that is not due to sun-fading or other extrinsic factors. The restriction alleles (A) are all dominant over no restriction (a). True black horses are all aa. It can be quite difficult to distinguish between true black and dark bay from phenotype alone. Since agouti is expressed only in the presence of at least one copy of the dominant extension allele (E) it is silenced in chesnuts who can be AA, Aa, or aa. |

Don Dun (1769 Brilliant - Regulus Tartar by Regulus) |

Most of the other known modifiers (champagne, cream, dun, pearl,

silver) are frequently referred to as "dilutions".

Only the cream dilution is known to occur in the Thoroughbred.

Mapped to the MATP locus on chromosome 21 the cream allele is

incompletely dominant. In heterozygotes (one cream allele, one

normal allele) some

lightening of the base coat will be expressed, turning chesnut

to palomino, bay to buckskin, and subtly softening black to a

shade some describe as "sooty". In homozygotes (two cream

alleles) the dilution of base coat colour is even more

pronounced. A peer-reviewed report published 2010 made the claim that "[a]ll Thoroughbred horses are homozygous non-cream". Don Dun (1769, by Brilliant - Regulus Tartar, by Regulus) is one of several early Thoroughbreds recorded as dun that were more likely buckskin. The cream dilution allele was almost certainly present in the TB founder population (Darcy's Yellow Turk, Oxford Dun Arabian, et al.). Occasional references to "light" bays and chesnuts in 19th and 20th century stud books suggest it may have persisted in the population at low level since then. It's presence in the contemporary TB population has been confirmed by genetic testing. |

Master Magpie (ch c 1905 Gallinule - Meddlesome by St. Gatien) |

"Chrome" (White) Distribution of white hair in the coat is controlled mainly, though by no means exclusively, by variations in the KIT complex on equine chromosome 3. Skin and eye colour may be affected as well. The resulting phenotypes range from little or no white to completely white. Genetic factors resulting in predominantly white horses are often lethal in the homozygous state. Genetic factors that result in white on one or more legs, large blazes and patches of white that do not cover a majority of the body are usually not lethal in the homozygous state. Both types of factors have been documented in the Thoroughbred. Widespread distribution of white hair intermixed with base coat colour hair is called roaning. When roaning occurs everywhere except the points (ears, mane, tail, legs) the horse is said to be a true "roan". True roan can be verified by genetic testing and has been documented in the Thoroughbred only as an apparent de novo mutation in some descendants of Catch A Bird (NZ 1982). While a great many Thoroughbreds have been and still are recorded or registered as "roan", this probably reflects the fact that roaning on the body is not at all uncommon when there is a significant amoung of white on the legs and face. In one particular white distribution pattern, known as rabicano and most notable for the white-streaked 'skunk tail' it produces, there can be intense roaning fanning out from the flank that may extend over the barrel and or/hip. Patterns that do not produce the skunk tail are usually referred to as "sabino". Genetic testing of sabino Thoroughbreds has revealed mutations in the KIT complex. The genetic mechanism that produces the rabicano pattern has not yet been identified. White and especially roaning can easily be mistaken for grey, which may explain why some registries have a 'one size fits all' grey/roan classification. This ambiguity could explain at least some occurrences of "grey" foals with non-grey sires and dams as recorded in the early stud books. |

|

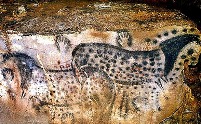

Spots &c Genetic testing has identified the Leopard complex spotting allele in horse remains from Pleistocene Europe, indicating that the spotted horses of Pech Merle probably reflect phenotypic variations observed by the artist(s). Mapped to equine chromosome 1, this trait persists in several contemporary breeds/types but is not known to occur in the Thoroughbred. |

The Tetrarch |

The flamboyant appearance of The Tetrarch (aka: "The Spotted Wonder") in his youth was due to Chubari spots, irregularly oval patches of lighter grey hair, which occasionally manifest themselves while grey is replacing the base coat colour. Dark spots of similar size on the hip and occasionally on the flank and barrel, most easily seen in chesnuts, are known as Bend Or spots. (These may have actually belonged to the horse registered as Tadcaster, but early records suggest that both foals had at least one such spot on a hip.) Very small patches of white hair concentrated near the topline between neck and tail are known as Birdcatcher ticking. A silvery flaxen streaked tail is called the "Gulastra plume" after an eponymous Arab who was recorded in the American Stud Book at a time Arabs were eligible for inclusion therein. It does, however, occur in Thoroughbreds unrelated to Gulastra, Cigar (1990, USA Horse Of The Year 1995, 1996) being one notable example. |

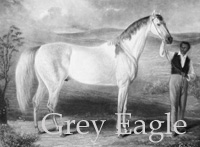

Grey Eagle |

Occasionally, greys will retain a patch of base coat colour. Evidence for this phenomenon in the

Thoroughbred appears in the founder population. The

Bloody-Shouldered Arabian was painted many times. Also of

note is Bloody Buttocks who was described in GSB as a grey Arabian "with a

red mark on his hip, from whence he derived his name". Another example is the American horse Grey Eagle (1835 gr c by Woodpecker - Ophelia, by Wild Medley) whose spot appears near his withers. Grey Eagle was painted by Edward Troye in 1841. His owner presented the painting to the steamship "Grey Eagle". It was destroyed when that vessel burned. Fortunately, it had been reproduced in mezzotint (Jordan & Halperin) by 'Spirit of the Times' in 1842. |

|

|

|